Monsieur Verdoux

Monsieur Verdoux Il Mostro

Il Mostro Kind Hearts and

Kind Hearts andCoronets

Serial Mom

Serial MomArsenic and Old Lace

RANTINGS AND RAVINGS

In the Loop may be a comedy, but it’s also one of the most depressing movies of the year. It’s political in a way only the British usually are—bitter, brittle and more bitchy than Noel Coward (House of Cards anyone). It’s also a study of contrasts between how the British get things done and how the Americans get things done. In England one bullies and threatens, at times becoming physically violent. To survive an assault, one simply stands up to it and refuses to let anyone get a leg up (a friend of mine says it’s all the outcome of British private schools and there are times you can almost hear someone say, “Sir, may I please have another”). In the U.S., one is manipulative and sneaky, dancing around everything, outfoxing someone while trying to find their weak spot. The only thing the two groups have in common is the number of four letter words they use. The story is all about the events leading up to a declaration of war between the U.S. and the Middle East. Though the country is never mentioned by name, it’s ridiculous not to realize the target is Iraq. Because of this, the movie begins to resemble French playwright Jean Giraudoux’s The Trojan War Will Not Take Place, in which a valiant Hector tries his best to stop a war that will not be stopped. In the end, even though there comes a moment when you think the good guys will win, it becomes clear that conflict is a foregone conclusion because the war with Iraq indeed did take place. The comedy then gives way to tragedy. The ensemble cast is first rate with Peter Capaldi the foul mouthed stand out doing his role of mid-level bureaucrat one better than the one he played in the terrific TV series, Torchwood: Children of Men. The script (by Jesse Armstrong, Simon Blackwell, Armando Iannucci—who also directed, Ian Martin and Tony Roche) is bollocksy brilliant, full of poetic vulgarities. The only problem here is that the script is so brilliant, it sometimes seems so carried away with itself, that one loses track of the some of the characters’ motivations. Somewhere along the way, I became a bit unclear just why some in England wanted to go to war and join forces with the U.S. and why others didn’t. See this as a double feature with Dr. Strangelove.

In the Informant! (with an exclamation point—excuse me), Matt Damon as Mark Whitacre joins the great sociopathic liars of the silver screen like Harriet Craig (Craig’s Wife), Stephen Glass (Shattered Glass), and Mary Tilford (The Children’s Hour). Not a bad group to be a member of. The story is about an FBI investigation into price fixing in the corn industry, but the real suspense is not if the FBI will make their case—the real suspense derives from how long Whitacre can keep up the lying and how often he can dig himself out of whatever hole he’s crawled into. I’m not sure it’s a brilliant performance. Damon is good, but there is a certain flatness to his performance. At the same time, there’s a certain flatness to everything: the cinematography, the bland 1970’s décor, the dated music by Marvin Hamlisch (though this last rises above the flatness). Of course, the 1970’s was a bland decade and director Steven Soderbergh seems to make the most of it and though I’m not sure how, it does seem to add something to the proceedings. The supporting cast also has that somewhat 1970’s look about them as well with the Smothers Brothers perhaps the most recognizable. It’s a well written entertainment (script by Scott Z. Burns) with perhaps its major flaw being the character of Ginger Whitacre, Whitacre’s wife, played by Melanie Lynskey. The author either couldn’t, or even worse, couldn’t be bothered, to try to understand what made Ginger tick. What little character she has is provided by Lynskey’s lovely, lilting voice. But the actress deserved better.

It’s a little difficult to determine why, and therefore somewhat annoying that, Coco Before Chanel is as enjoyable as it is. After all, it’s a fairly standard biopic, as sturdy and strong as anything put out by Warner Brothers in the 1930’s. At the same time, it does have one thing many biopics don’t; it doesn’t try to tell us how important, how great, how significant the subject is. Coco Before Chanel imparts its story somewhat simply and to the point; not as if this is a biography of the greatest fashion designer of the 20th century, but as if it was nothing more than a study of what it was like to be a woman who wanted a career when fin de siècle was in the air. It also doesn’t try to bite off more than it should chew. The story line covers only a relatively short period of Chanel’s life, from the time she left an orphanage to the time she opened her first dressmaking shop, what appears to be but a few years.

It’s a little difficult to determine why, and therefore somewhat annoying that, Coco Before Chanel is as enjoyable as it is. After all, it’s a fairly standard biopic, as sturdy and strong as anything put out by Warner Brothers in the 1930’s. At the same time, it does have one thing many biopics don’t; it doesn’t try to tell us how important, how great, how significant the subject is. Coco Before Chanel imparts its story somewhat simply and to the point; not as if this is a biography of the greatest fashion designer of the 20th century, but as if it was nothing more than a study of what it was like to be a woman who wanted a career when fin de siècle was in the air. It also doesn’t try to bite off more than it should chew. The story line covers only a relatively short period of Chanel’s life, from the time she left an orphanage to the time she opened her first dressmaking shop, what appears to be but a few years. My One is Only is an ice cream sundae that comes equipped with whip cream and a cherry on top. The whip cream is provided by Mark Rendall’s performance as Robbie, the somewhat swishy younger brother who gets the running gag of always landing the lead in a school play (including Oedipus of all things—what high school does Oedipus Rex) but never actually making it on stage. The cherry is the revelation that the central character in all this, Robbie’s older brother George, is actually a famous movie star—George Hamilton. The ice cream is provided by Renee Zellwegger as Anne Deveraux, a mother who divorces her cheating husband, takes her two kids, and goes gunning for old boyfriends to see if she can marry into money.

My One is Only is an ice cream sundae that comes equipped with whip cream and a cherry on top. The whip cream is provided by Mark Rendall’s performance as Robbie, the somewhat swishy younger brother who gets the running gag of always landing the lead in a school play (including Oedipus of all things—what high school does Oedipus Rex) but never actually making it on stage. The cherry is the revelation that the central character in all this, Robbie’s older brother George, is actually a famous movie star—George Hamilton. The ice cream is provided by Renee Zellwegger as Anne Deveraux, a mother who divorces her cheating husband, takes her two kids, and goes gunning for old boyfriends to see if she can marry into money. Fanny Brawne is also a designer of clothes and from what I understand, she was suppose to have been known, at least among friends, for her taste. Personally, I found her fashions, as seen in the movie Bright Star, a bio film of her relationship with the poet John Keats, to be rather gaudy and all over the place. The same could not be said of the movie written and directed by Jane Campion. It’s a down to earth, anti-romantic depiction of a very romantic love story set during the romantic period. I greatly admired what Campion did with Henry James’ Portrait of a Lady, but I’m afraid I found this to be as dull as any Ivory/Merchant concoction. Even more dishwatery perhaps. I’m not sure why. It could be that the two leads, Abbie Cornish as Fannie and Ben Whishaw as Keats, who seem to be perfectly fine actors, just didn’t have enough fire in their roles. Perhaps this was Champion’s choice as well. Perhaps the last thing she wanted was the grand passion of Lawrence Olivier and Merle Oberon in Wuthering Heights. But for me, it didn’t even have the restrained sexual tension of a Jane Austen novel. The most interesting performance is given by Paul Schneider as the misogynistic cad Charles Armitage Brown who has the most fascinating line readings of any actor in some time. One almost hates him not just for his lines, but for the way he says them.

Fanny Brawne is also a designer of clothes and from what I understand, she was suppose to have been known, at least among friends, for her taste. Personally, I found her fashions, as seen in the movie Bright Star, a bio film of her relationship with the poet John Keats, to be rather gaudy and all over the place. The same could not be said of the movie written and directed by Jane Campion. It’s a down to earth, anti-romantic depiction of a very romantic love story set during the romantic period. I greatly admired what Campion did with Henry James’ Portrait of a Lady, but I’m afraid I found this to be as dull as any Ivory/Merchant concoction. Even more dishwatery perhaps. I’m not sure why. It could be that the two leads, Abbie Cornish as Fannie and Ben Whishaw as Keats, who seem to be perfectly fine actors, just didn’t have enough fire in their roles. Perhaps this was Champion’s choice as well. Perhaps the last thing she wanted was the grand passion of Lawrence Olivier and Merle Oberon in Wuthering Heights. But for me, it didn’t even have the restrained sexual tension of a Jane Austen novel. The most interesting performance is given by Paul Schneider as the misogynistic cad Charles Armitage Brown who has the most fascinating line readings of any actor in some time. One almost hates him not just for his lines, but for the way he says them.  Evangelion 1.0 You Are (Not) Alone (try saying that ten times fast) is also what I would call a curiosity. Set in the future when an evil organization sends super killing machines to destroy some city in Japan (I guess Godzilla and Mothra were previously indisposed) and there’s only one organization that can stop them. Each evil machine seems to learn from the defeat of the previous one so that old strategies and methods of defense quickly become obsolete (it’s just as true in modern warfare, though it takes a little longer). In other words, it’s like a video game where each victory isn’t a victory, but just jumps you up another level. In true anime form, the story (by Hideaki Anno, who also surpervised the directing) holds together kinda, sorta, but never really makes much sense, though it’s difficult to say whether this might at least partially be due to this being the second installment in a series. True, I haven’t seen the first one, but I doubt it would make that much of a difference. The animation is often beautiful and there are some fun scenes (though also one disturbing one where a teenager ends up lying naked on top of his naked sister—it’s suppose to be tres droll, but is more a tad disturbing). In the end, it falls to two people, twins (the aforementioned brother and sister, but with their clothes on), the offspring of the scientist who invented the weapon that can defeat the bad guys, to save their city. For some reason, these two are the only ones who can operate Evangeline, the robotic fighting machine that is mankind’s only hope, and the operating of it leads to all sorts of “why doesn’t daddy love me” conflicts. The male twin is also the lead. He spends much of his down time when he’s not saving the world being bullied at his school and pushed around by other people, which seems to me to be an odd way to treat the only person who can stop an evil organization from destroying the world. But this is anime, after all.

Evangelion 1.0 You Are (Not) Alone (try saying that ten times fast) is also what I would call a curiosity. Set in the future when an evil organization sends super killing machines to destroy some city in Japan (I guess Godzilla and Mothra were previously indisposed) and there’s only one organization that can stop them. Each evil machine seems to learn from the defeat of the previous one so that old strategies and methods of defense quickly become obsolete (it’s just as true in modern warfare, though it takes a little longer). In other words, it’s like a video game where each victory isn’t a victory, but just jumps you up another level. In true anime form, the story (by Hideaki Anno, who also surpervised the directing) holds together kinda, sorta, but never really makes much sense, though it’s difficult to say whether this might at least partially be due to this being the second installment in a series. True, I haven’t seen the first one, but I doubt it would make that much of a difference. The animation is often beautiful and there are some fun scenes (though also one disturbing one where a teenager ends up lying naked on top of his naked sister—it’s suppose to be tres droll, but is more a tad disturbing). In the end, it falls to two people, twins (the aforementioned brother and sister, but with their clothes on), the offspring of the scientist who invented the weapon that can defeat the bad guys, to save their city. For some reason, these two are the only ones who can operate Evangeline, the robotic fighting machine that is mankind’s only hope, and the operating of it leads to all sorts of “why doesn’t daddy love me” conflicts. The male twin is also the lead. He spends much of his down time when he’s not saving the world being bullied at his school and pushed around by other people, which seems to me to be an odd way to treat the only person who can stop an evil organization from destroying the world. But this is anime, after all. Zombieland is what is known as a post modern zombie movie, i.e., it’s not about how we got zombie’s so much as being about how we live in a world in which zombies are assumed. It’s also post modern in the way it is self aware of what it is, which is very tongue in cheek, at least when the cheeks are not throwing up vile vomit. It revolves around Columbus, a germaphobic loner played by Jessie Eisenberg in his usual nerdy persona. Columbus has 32 rules for surviving zombies, all very smart ones. Unfortunately (for me and apparently for me only, because everyone I talk to loooooooves this movie), the writers Rhett Reese and Paul Wernick don’t seem to think they have to play by any rules at all, especially when it comes to the actions of the characters, who tend to do things more in accordance with the style and objective of the authors rather than what they would really do in such a situation. This means that the characters are extremely smart when Reese and Wernick need them to be, and extremely and inexcusably stupid when Reese and Wernick need them to be. On the plus side, this allows for some clever scenes, especially a very funny Saturday Night Live type sketch starring Bill Murray in a cameo (though the basic comic idea here has already been done in Shawn of the Dead, a movie I preferred overall). At its worst, you can feel nagged and annoyed at the arbitrary nature of much of it. At its best, you can just relax (well, relax as much as you can with the fear that the next bathroom door you open will have a zombie in it) and go along for the ride. The characterizations and dialogue are above average, the most clever aspect of it being that though Columbus’s obsessive compulsiveness and various phobias are the parts of his personalities responsible for his survival (imagine a world in which only Monk and Felix Unger survive), at the same time, the arrival of zombies is the impetus that cures him of his germaphobia and saves him from his destiny of masturbation being his only method of sexual release. Abigail Breslin, as a 12 year old con artist, gives perhaps the best performance here (she’s almost unrecognizable). Though everybody works very hard, both behind and in front of the camera, and the apocalyptic scenery of empty streets and deserted landscapes have a certain beauty to them, in the end, for me, it never really rises to what it wants to be.

Zombieland is what is known as a post modern zombie movie, i.e., it’s not about how we got zombie’s so much as being about how we live in a world in which zombies are assumed. It’s also post modern in the way it is self aware of what it is, which is very tongue in cheek, at least when the cheeks are not throwing up vile vomit. It revolves around Columbus, a germaphobic loner played by Jessie Eisenberg in his usual nerdy persona. Columbus has 32 rules for surviving zombies, all very smart ones. Unfortunately (for me and apparently for me only, because everyone I talk to loooooooves this movie), the writers Rhett Reese and Paul Wernick don’t seem to think they have to play by any rules at all, especially when it comes to the actions of the characters, who tend to do things more in accordance with the style and objective of the authors rather than what they would really do in such a situation. This means that the characters are extremely smart when Reese and Wernick need them to be, and extremely and inexcusably stupid when Reese and Wernick need them to be. On the plus side, this allows for some clever scenes, especially a very funny Saturday Night Live type sketch starring Bill Murray in a cameo (though the basic comic idea here has already been done in Shawn of the Dead, a movie I preferred overall). At its worst, you can feel nagged and annoyed at the arbitrary nature of much of it. At its best, you can just relax (well, relax as much as you can with the fear that the next bathroom door you open will have a zombie in it) and go along for the ride. The characterizations and dialogue are above average, the most clever aspect of it being that though Columbus’s obsessive compulsiveness and various phobias are the parts of his personalities responsible for his survival (imagine a world in which only Monk and Felix Unger survive), at the same time, the arrival of zombies is the impetus that cures him of his germaphobia and saves him from his destiny of masturbation being his only method of sexual release. Abigail Breslin, as a 12 year old con artist, gives perhaps the best performance here (she’s almost unrecognizable). Though everybody works very hard, both behind and in front of the camera, and the apocalyptic scenery of empty streets and deserted landscapes have a certain beauty to them, in the end, for me, it never really rises to what it wants to be.  9 is what I usually call a curiosity; something that is certainly interesting, but exactly what I’m suppose to make of it is a bit of a mystery. In movies like 2001: A Space Odyssey, Blade Runner and Screamers, the question is asked, if one can’t determine the difference between a robot, android, clone etc. and a human being, is there one? In 9, the answer is assumed and it is no, there is none, they are the same. It’s questionable whether this works out in a satisfactorily dramatic manner because in many ways 9 answers the question the way the authors Pamela Pettler and Shane Acker (who also directed) may not have intended—they want to suggest there is no difference, but everything in the movie screams the opposite. These dolls may have self awareness and emotions, but they just don’t make it as replacements for human beings. For example, they can’t reproduce (so even if they do survive, it doesn’t mean anything to the continuation of the human race). Though some are older than others, they can’t age (though presumably they can decay). And fortunately for the producers and directors and the MPAA ratings board, they can’t go through puberty, much less have sex (the authors even go to the trouble of creating one female doll—only one, mind you, I suppose that’s all females are worth in this futuristic world—but to what end is hard to say, except to get little girls into the audience). And so in the end, it’s a little difficult to become fully invested emotionally in some dolls desperately trying to survive a post apocalyptic world where not only are there no more human beings, there doesn’t seem to be life forms left of any sort.

9 is what I usually call a curiosity; something that is certainly interesting, but exactly what I’m suppose to make of it is a bit of a mystery. In movies like 2001: A Space Odyssey, Blade Runner and Screamers, the question is asked, if one can’t determine the difference between a robot, android, clone etc. and a human being, is there one? In 9, the answer is assumed and it is no, there is none, they are the same. It’s questionable whether this works out in a satisfactorily dramatic manner because in many ways 9 answers the question the way the authors Pamela Pettler and Shane Acker (who also directed) may not have intended—they want to suggest there is no difference, but everything in the movie screams the opposite. These dolls may have self awareness and emotions, but they just don’t make it as replacements for human beings. For example, they can’t reproduce (so even if they do survive, it doesn’t mean anything to the continuation of the human race). Though some are older than others, they can’t age (though presumably they can decay). And fortunately for the producers and directors and the MPAA ratings board, they can’t go through puberty, much less have sex (the authors even go to the trouble of creating one female doll—only one, mind you, I suppose that’s all females are worth in this futuristic world—but to what end is hard to say, except to get little girls into the audience). And so in the end, it’s a little difficult to become fully invested emotionally in some dolls desperately trying to survive a post apocalyptic world where not only are there no more human beings, there doesn’t seem to be life forms left of any sort. The Baader Meinhof Complex is the last movie I needed to see in order to fill in the best foreign language film nominees for the 2008 Oscars. TMBC (as I affectionately call it) is an exciting and exhilarating movie that you can’t stop watching. Whatever else you might say about it, you can’t say it’s boring. But at the same time, though based on a true story, once I was through watching it, I had more questions than answers. As the credits took to the screen, I realized I still wasn’t sure who the Complex was or what they were trying to do, or more accurately, what their short terms goals were in trying to achieve their long term goals. Because of this, the most engaging character was Horst Herold, the head of the German police force, the man brought in to bring them down (portrayed by the great Bruno Ganz who also played Adolf Hitler in Downfall—coincidence or conspiracy, you be the judge). Herold didn’t just want to arrest the Complex, he wanted to get rid of the root causes of their existence. Since no one else agreed with him, today with have this film. One does feel for Harold. After all, if the screenwriters Bernd Eichinger and Uli Edel (who also directed) couldn’t help us understand what it was all about, it’s a bit hard to believe that Herold could fare much better. At times it feels like a final round of Wheel of Fortune in which the audience has been given the most commonly used letters and vowels, but must now guess a few more and hope to get enough to figure out the final phrase. The best known here of the actors in the U.S. is probably Moritz (Run, Lola, Run; The Experiment; The Walker—the last as Woody Harrelson’s lover) Bleibtreu. He plays the racist, chauvinistic Andreas Baader as if he were the schoolyard bully who thought he was entitled to everyone’s lunch money and couldn’t understand why everyone else didn’t agree with him. He’s very good. All the actors are. In the end, you can’t help but wonder whether the whole thing worked better for a German audience who may have been better able to fill in the blanks more easily that someone in the U.S., in the same way we might be able to fill in the blanks about a movie about the Kent State shootings. But whatever the movie’s faults, it is highly entertaining.

The Baader Meinhof Complex is the last movie I needed to see in order to fill in the best foreign language film nominees for the 2008 Oscars. TMBC (as I affectionately call it) is an exciting and exhilarating movie that you can’t stop watching. Whatever else you might say about it, you can’t say it’s boring. But at the same time, though based on a true story, once I was through watching it, I had more questions than answers. As the credits took to the screen, I realized I still wasn’t sure who the Complex was or what they were trying to do, or more accurately, what their short terms goals were in trying to achieve their long term goals. Because of this, the most engaging character was Horst Herold, the head of the German police force, the man brought in to bring them down (portrayed by the great Bruno Ganz who also played Adolf Hitler in Downfall—coincidence or conspiracy, you be the judge). Herold didn’t just want to arrest the Complex, he wanted to get rid of the root causes of their existence. Since no one else agreed with him, today with have this film. One does feel for Harold. After all, if the screenwriters Bernd Eichinger and Uli Edel (who also directed) couldn’t help us understand what it was all about, it’s a bit hard to believe that Herold could fare much better. At times it feels like a final round of Wheel of Fortune in which the audience has been given the most commonly used letters and vowels, but must now guess a few more and hope to get enough to figure out the final phrase. The best known here of the actors in the U.S. is probably Moritz (Run, Lola, Run; The Experiment; The Walker—the last as Woody Harrelson’s lover) Bleibtreu. He plays the racist, chauvinistic Andreas Baader as if he were the schoolyard bully who thought he was entitled to everyone’s lunch money and couldn’t understand why everyone else didn’t agree with him. He’s very good. All the actors are. In the end, you can’t help but wonder whether the whole thing worked better for a German audience who may have been better able to fill in the blanks more easily that someone in the U.S., in the same way we might be able to fill in the blanks about a movie about the Kent State shootings. But whatever the movie’s faults, it is highly entertaining. Paris is a series of several different stories about people living in Paris that sort of, kind of, but never really, and certainly never convincingly, interlock. The most successful of the several story lines is the one with Romain Duris, he of the odd chest hair and the perpetual sneer that even a goatee can’t fully hide. Duris is one of the finest young French actors today, the male Audrey Tautou (I call him that because he is an ingénue and is in every other French film these days—he’s even played a young Moliere while Tautou has played a young Coco Chanel). Duris plays a dancer with a Follies Bergere looking type show who develops a heart condition that will kill him if he’s unable to get a transplant. Juliette Binoche, one of the more amazing French actors, plays his sister who moves in with her children in order to take care of them (it’s wonderful seeing these two together). The other stories, with some of the more recognizable French characters actors these days, all have their moments, but are never as interesting or dramatically satisfying as the one with Duris (who achieves true pathos in his final scene). The others also all wear out their welcome long before they should; they keep on going and going like the Energizer Bunny and become just as annoying. The screenplay, by the director Cedric Klapisch, known for the much more enjoyable While the Cat’s Away and L’auberge espagnol, often feels like a movie based on a book of short stories which the screenwriter is desperately trying to weave together into a satisfying whole (can you say Short Cuts). But it never completely works.

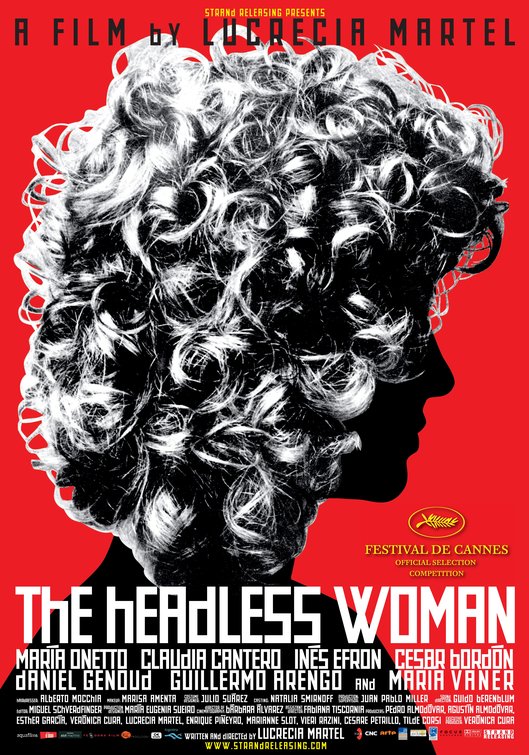

Paris is a series of several different stories about people living in Paris that sort of, kind of, but never really, and certainly never convincingly, interlock. The most successful of the several story lines is the one with Romain Duris, he of the odd chest hair and the perpetual sneer that even a goatee can’t fully hide. Duris is one of the finest young French actors today, the male Audrey Tautou (I call him that because he is an ingénue and is in every other French film these days—he’s even played a young Moliere while Tautou has played a young Coco Chanel). Duris plays a dancer with a Follies Bergere looking type show who develops a heart condition that will kill him if he’s unable to get a transplant. Juliette Binoche, one of the more amazing French actors, plays his sister who moves in with her children in order to take care of them (it’s wonderful seeing these two together). The other stories, with some of the more recognizable French characters actors these days, all have their moments, but are never as interesting or dramatically satisfying as the one with Duris (who achieves true pathos in his final scene). The others also all wear out their welcome long before they should; they keep on going and going like the Energizer Bunny and become just as annoying. The screenplay, by the director Cedric Klapisch, known for the much more enjoyable While the Cat’s Away and L’auberge espagnol, often feels like a movie based on a book of short stories which the screenwriter is desperately trying to weave together into a satisfying whole (can you say Short Cuts). But it never completely works.  I saw The Headless Woman last year at the AFI film festival and it made the Howies, my list of the best films of the year (well, in this case the shorter list of films that were the best but only played one night stands at film festivals and such—I wasn’t sure whether I should include movies like that with my Howies, but since I couldn’t be sure, especially these days, that these films would ever open here, I went ahead and did it, even if it might screw up my list for the next year if they did open), Oh, and Maria Onetto made my best actress list. Whether one likes this film or not may depend on temperament. I found it incredibly engrossing, other people find it excruciatingly slow. In fact, The Headless Woman could actually be the sort of movie those friends of yours who won’t go with you to foreign films use as an example why. Onetto plays Veronica, a woman who accidentally hits something in the road and then begins acting oddly: she loses her memory, but tries to pretend as if she hasn’t. This may be the make or break section of the movie. If you don’t realize what is going on, it’s quite possible you will be bored and want to become headless yourself. If you do catch on, then you might find the suspense unbearable and the story line fascinating. When Veronica does recover her memory, she believes she might have hit a child with her car and the story then shows how her husband and lover work to first convince her she only hit a dog; and then when it seems she was right, show how the two cover up the accident. The moral quandary here is interesting. Veronica was involved in a hit and run, but she didn’t leave the scene maliciously—she lost her memory. You know the police will probably never believe her, so you end up hoping she gets away with it; at the same time, you feel a tad queasy at the idea of a crime going unpunished. In the end, though something highly melodramatic happened, there’s little melodrama or heavy breathing here, which again may alienate movie goers use to tent pole films or American film noir with numerous chase scenes and over the top action sequences. It’s a quiet film filled with quiet moments of quiet intensity. The writer director is Lucrecia Martel and I’m one of the few people who didn’t seem to care for her last film The Holy Girl, which I did find slow. What a difference a year can make.

I saw The Headless Woman last year at the AFI film festival and it made the Howies, my list of the best films of the year (well, in this case the shorter list of films that were the best but only played one night stands at film festivals and such—I wasn’t sure whether I should include movies like that with my Howies, but since I couldn’t be sure, especially these days, that these films would ever open here, I went ahead and did it, even if it might screw up my list for the next year if they did open), Oh, and Maria Onetto made my best actress list. Whether one likes this film or not may depend on temperament. I found it incredibly engrossing, other people find it excruciatingly slow. In fact, The Headless Woman could actually be the sort of movie those friends of yours who won’t go with you to foreign films use as an example why. Onetto plays Veronica, a woman who accidentally hits something in the road and then begins acting oddly: she loses her memory, but tries to pretend as if she hasn’t. This may be the make or break section of the movie. If you don’t realize what is going on, it’s quite possible you will be bored and want to become headless yourself. If you do catch on, then you might find the suspense unbearable and the story line fascinating. When Veronica does recover her memory, she believes she might have hit a child with her car and the story then shows how her husband and lover work to first convince her she only hit a dog; and then when it seems she was right, show how the two cover up the accident. The moral quandary here is interesting. Veronica was involved in a hit and run, but she didn’t leave the scene maliciously—she lost her memory. You know the police will probably never believe her, so you end up hoping she gets away with it; at the same time, you feel a tad queasy at the idea of a crime going unpunished. In the end, though something highly melodramatic happened, there’s little melodrama or heavy breathing here, which again may alienate movie goers use to tent pole films or American film noir with numerous chase scenes and over the top action sequences. It’s a quiet film filled with quiet moments of quiet intensity. The writer director is Lucrecia Martel and I’m one of the few people who didn’t seem to care for her last film The Holy Girl, which I did find slow. What a difference a year can make. Still Walking is not necessarily the best title for a film. Whenever I think of it, I’m reminded of those scenes in movies where tourists are taken on a tour of the White House and the guide says “We’re walking, we’re walking”. And I’m still uncertain just what the title is suppose to tell us. But Still Walking, from Japan, may be another one of those movies friends use as the excuse they won’t go to something subtitled with you. It’s about a family that meets once a year to remember the passing of their oldest son who died while rescuing someone else from drowning. You might think, especially if you’re American, that there would be a lot of sturm and drang; but in actuality, it’s all still moments, unspoken grievances and repressed emotions. It’s a film that is about nothing, while being about everything. The conflicts are the familiar ones found in families everywhere: the daughter wants to move in with the parents to take care of them, but the mother doesn’t want it because it will be a nuisance and interfere in her routine; the father is distant father and the mother nips at the bottle a bit too much; and most central, the younger son has donned the difficult mantle of seniority now that the elder, but favorite, son has died, but he is also saddled with a father he can’t please. The most chilling scene is when the mother reveals the real reason she insists on inviting every year the man her son rescued, a pathetic, overweight, awkward, young slacker who can’t find his way in life. What seals the emotional punch is the off the cuff way she lets her son know. The Japanese family film in which the members don’t yell and scream at each other like the Tyrone’s of Long Day’s Journey Into Night, but instead live their conflicts quietly and with dignity (for better and for worse), is a Japanese subgenre all its own. The most famous practitioner of this sort of film known in the U.S. is probably Ozu. Here the writer/director is Hirokazu Koreeda, the creator of the heartbreakingly beautiful Afterlife and the moving Nobody Knows. Still Walking is one of the finest films of the year.

Still Walking is not necessarily the best title for a film. Whenever I think of it, I’m reminded of those scenes in movies where tourists are taken on a tour of the White House and the guide says “We’re walking, we’re walking”. And I’m still uncertain just what the title is suppose to tell us. But Still Walking, from Japan, may be another one of those movies friends use as the excuse they won’t go to something subtitled with you. It’s about a family that meets once a year to remember the passing of their oldest son who died while rescuing someone else from drowning. You might think, especially if you’re American, that there would be a lot of sturm and drang; but in actuality, it’s all still moments, unspoken grievances and repressed emotions. It’s a film that is about nothing, while being about everything. The conflicts are the familiar ones found in families everywhere: the daughter wants to move in with the parents to take care of them, but the mother doesn’t want it because it will be a nuisance and interfere in her routine; the father is distant father and the mother nips at the bottle a bit too much; and most central, the younger son has donned the difficult mantle of seniority now that the elder, but favorite, son has died, but he is also saddled with a father he can’t please. The most chilling scene is when the mother reveals the real reason she insists on inviting every year the man her son rescued, a pathetic, overweight, awkward, young slacker who can’t find his way in life. What seals the emotional punch is the off the cuff way she lets her son know. The Japanese family film in which the members don’t yell and scream at each other like the Tyrone’s of Long Day’s Journey Into Night, but instead live their conflicts quietly and with dignity (for better and for worse), is a Japanese subgenre all its own. The most famous practitioner of this sort of film known in the U.S. is probably Ozu. Here the writer/director is Hirokazu Koreeda, the creator of the heartbreakingly beautiful Afterlife and the moving Nobody Knows. Still Walking is one of the finest films of the year.