The Most Dangerous Man in America is one of the five documentaries nominated for a 2009 Oscar. I grew up during the period covered in the film and though, as a teenager in Corpus Christi, Texas, politics didn’t really interest me that much (I escaped the draft by one year), I do have memories of some of the events related in this movie. As I got older, I did come to realize that the American people were often lied to by their government in regards to Viet Nam (the attacks on U.S. ships in the Gulf of Tonkin were pure fabrication, for example). At the same time, it still never ceases to amaze me the extent to which the deception went. I don’t know why it should. One of the rather scary aspects of the film is just how much it reminds me of our involvement in Iraq and the government’s lying about weapons of mass destruction. But why should the government of the past be any different than the government of the present? Even more nightmarish, perhaps, is to realize that Henry Kissinger was actually the voice of reason in a White House that, under Richard Nixon, wanted to drop a nuclear bomb on North Viet Nam. It’s narrated by many of the people who actually took part in the events, as well as by the title hero himself, Daniel Ellsberg, still alive and still protesting. He started out as a hawk and conservative, but came to realize that the war had to be stopped and hoped that releasing the top secret Pentagon Papers, which revealed the history of the U.S. involvement in the Southeast Asia from as far back as Truman, would do just that. It didn’t, at least not directly, much to Ellsberg’s disappointment. Nixon was reelected in spite of the Papers publication. But it did put such pressure on the paranoid White House that Nixon started doing things like having people break into Ellsberg’s psychiatrist office and try to break into the Democratic headquarters at Watergate. The shame of the crimes forced Nixon to resign and end the war. Perhaps the greatest triumph of the Papers’ publication was the Supreme Court ruling allowing them to be published, which meant that just because the government says something is top secret, that doesn’t mean it should be. For those of you who like a love story, this also has that as well; there is a sweet through line of Daniel’s wooing of his second wife Patricia, an anti-war activist. You can still see the love in their eyes. This is a strong, fascinating documentary, clearly told by the writers Michael Chandler, Judith Ehrlich (who also directed), Rick Goldsmith (who also directed) and Lawrence Lerew. See it on a double bill with The Fog of War, Errol Morris’s filming of one long monologue by the former U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara who turned against the war after supporting it and lying about it. He also makes an appearance in the movie in old news footage where he gets off a plane after being briefed by Ellsberg about the hopelessness of the war. McNamara fully agreed with Ellsberg, but there he is, telling reporters that victory is right around the corner.

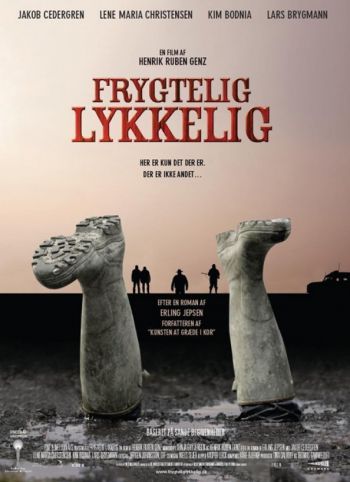

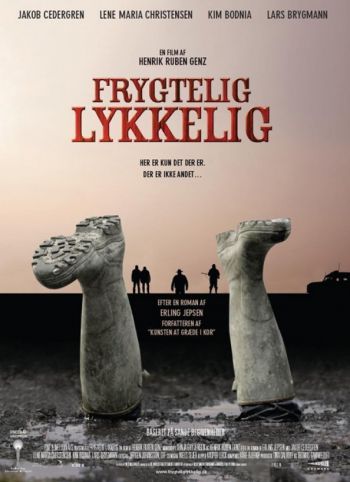

Terribly Happy has an Oscar connection as well. It was Denmark’s official entry in the foreign film category. It wasn’t chosen, however. To be honest, I can’t say I’m that disappointed. It’s about a police officer in Copenhagen who pulls a gun on his wife when he catches her with another man. For recovery (and punishment), he’s sent to a very, very, very small town that has its own ways of doing things, like killing and dumping people they don’t like in a bog (it almost reads like a very, very, very serious version of Hot Fuzz). The officer is pursued sexually by the wife of the town alpha male and bully, who often beats her for flirting with other men. This leads to tragedy for the wife and bully who end up getting killed by the officer, crimes covered up by the town. From that summary, it sounds like my cup of tea. But Terribly Happy never grabbed me. I wasn’t always sure why. I know that at the beginning the officer comes across as so incompetent I had little interest or sympathy for him. He seemed over his head, but not because the town had its own set of rules, but because he didn’t know what he was doing. The killing of the wife seemed a bit forced and unintentionally funny. And the ending where the town joins forces to stop the officer from returning to Copenhagen by threatening to tell the authorities what really happened didn’t make sense to me. I didn’t know why they wanted to keep this guy around. He’s not the most popular addition to a party. And why you would want to have someone around who got away with killing two people is beyond me; after all, the more someone kills and gets away with it, the more likely he is to kill again. And the same people who didn’t want him to call the police after the wife died because secrets of the town would come out, not seem to suddenly have no problem going to the police themselves. What would they do if the officer called their bluff? They’d be in almost as much trouble as he would. The screenplay is by Dunja Gry Jensen and the director Henrik Ruben Genz. There’s something about the unusual setting and the dark, Scandanavian mood about the whole thing that is somewhat interesting in itself. It tries to be different, character and atmosphere rather than formula directed and I wanted to be involved. I’m also willing to concede that it was me and not the film. But I just couldn’t get that terribly happy about it.

The Most Dangerous Man in America is one of the five documentaries nominated for a 2009 Oscar. I grew up during the period covered in the film and though, as a teenager in Corpus Christi, Texas, politics didn’t really interest me that much (I escaped the draft by one year), I do have memories of some of the events related in this movie. As I got older, I did come to realize that the American people were often lied to by their government in regards to Viet Nam (the attacks on U.S. ships in the Gulf of Tonkin were pure fabrication, for example). At the same time, it still never ceases to amaze me the extent to which the deception went. I don’t know why it should. One of the rather scary aspects of the film is just how much it reminds me of our involvement in Iraq and the government’s lying about weapons of mass destruction. But why should the government of the past be any different than the government of the present? Even more nightmarish, perhaps, is to realize that Henry Kissinger was actually the voice of reason in a White House that, under Richard Nixon, wanted to drop a nuclear bomb on North Viet Nam. It’s narrated by many of the people who actually took part in the events, as well as by the title hero himself, Daniel Ellsberg, still alive and still protesting. He started out as a hawk and conservative, but came to realize that the war had to be stopped and hoped that releasing the top secret Pentagon Papers, which revealed the history of the U.S. involvement in the Southeast Asia from as far back as Truman, would do just that. It didn’t, at least not directly, much to Ellsberg’s disappointment. Nixon was reelected in spite of the Papers publication. But it did put such pressure on the paranoid White House that Nixon started doing things like having people break into Ellsberg’s psychiatrist office and try to break into the Democratic headquarters at Watergate. The shame of the crimes forced Nixon to resign and end the war. Perhaps the greatest triumph of the Papers’ publication was the Supreme Court ruling allowing them to be published, which meant that just because the government says something is top secret, that doesn’t mean it should be. For those of you who like a love story, this also has that as well; there is a sweet through line of Daniel’s wooing of his second wife Patricia, an anti-war activist. You can still see the love in their eyes. This is a strong, fascinating documentary, clearly told by the writers Michael Chandler, Judith Ehrlich (who also directed), Rick Goldsmith (who also directed) and Lawrence Lerew. See it on a double bill with The Fog of War, Errol Morris’s filming of one long monologue by the former U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara who turned against the war after supporting it and lying about it. He also makes an appearance in the movie in old news footage where he gets off a plane after being briefed by Ellsberg about the hopelessness of the war. McNamara fully agreed with Ellsberg, but there he is, telling reporters that victory is right around the corner.

The Most Dangerous Man in America is one of the five documentaries nominated for a 2009 Oscar. I grew up during the period covered in the film and though, as a teenager in Corpus Christi, Texas, politics didn’t really interest me that much (I escaped the draft by one year), I do have memories of some of the events related in this movie. As I got older, I did come to realize that the American people were often lied to by their government in regards to Viet Nam (the attacks on U.S. ships in the Gulf of Tonkin were pure fabrication, for example). At the same time, it still never ceases to amaze me the extent to which the deception went. I don’t know why it should. One of the rather scary aspects of the film is just how much it reminds me of our involvement in Iraq and the government’s lying about weapons of mass destruction. But why should the government of the past be any different than the government of the present? Even more nightmarish, perhaps, is to realize that Henry Kissinger was actually the voice of reason in a White House that, under Richard Nixon, wanted to drop a nuclear bomb on North Viet Nam. It’s narrated by many of the people who actually took part in the events, as well as by the title hero himself, Daniel Ellsberg, still alive and still protesting. He started out as a hawk and conservative, but came to realize that the war had to be stopped and hoped that releasing the top secret Pentagon Papers, which revealed the history of the U.S. involvement in the Southeast Asia from as far back as Truman, would do just that. It didn’t, at least not directly, much to Ellsberg’s disappointment. Nixon was reelected in spite of the Papers publication. But it did put such pressure on the paranoid White House that Nixon started doing things like having people break into Ellsberg’s psychiatrist office and try to break into the Democratic headquarters at Watergate. The shame of the crimes forced Nixon to resign and end the war. Perhaps the greatest triumph of the Papers’ publication was the Supreme Court ruling allowing them to be published, which meant that just because the government says something is top secret, that doesn’t mean it should be. For those of you who like a love story, this also has that as well; there is a sweet through line of Daniel’s wooing of his second wife Patricia, an anti-war activist. You can still see the love in their eyes. This is a strong, fascinating documentary, clearly told by the writers Michael Chandler, Judith Ehrlich (who also directed), Rick Goldsmith (who also directed) and Lawrence Lerew. See it on a double bill with The Fog of War, Errol Morris’s filming of one long monologue by the former U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara who turned against the war after supporting it and lying about it. He also makes an appearance in the movie in old news footage where he gets off a plane after being briefed by Ellsberg about the hopelessness of the war. McNamara fully agreed with Ellsberg, but there he is, telling reporters that victory is right around the corner. Terribly Happy has an Oscar connection as well. It was Denmark’s official entry in the foreign film category. It wasn’t chosen, however. To be honest, I can’t say I’m that disappointed. It’s about a police officer in Copenhagen who pulls a gun on his wife when he catches her with another man. For recovery (and punishment), he’s sent to a very, very, very small town that has its own ways of doing things, like killing and dumping people they don’t like in a bog (it almost reads like a very, very, very serious version of Hot Fuzz). The officer is pursued sexually by the wife of the town alpha male and bully, who often beats her for flirting with other men. This leads to tragedy for the wife and bully who end up getting killed by the officer, crimes covered up by the town. From that summary, it sounds like my cup of tea. But Terribly Happy never grabbed me. I wasn’t always sure why. I know that at the beginning the officer comes across as so incompetent I had little interest or sympathy for him. He seemed over his head, but not because the town had its own set of rules, but because he didn’t know what he was doing. The killing of the wife seemed a bit forced and unintentionally funny. And the ending where the town joins forces to stop the officer from returning to Copenhagen by threatening to tell the authorities what really happened didn’t make sense to me. I didn’t know why they wanted to keep this guy around. He’s not the most popular addition to a party. And why you would want to have someone around who got away with killing two people is beyond me; after all, the more someone kills and gets away with it, the more likely he is to kill again. And the same people who didn’t want him to call the police after the wife died because secrets of the town would come out, not seem to suddenly have no problem going to the police themselves. What would they do if the officer called their bluff? They’d be in almost as much trouble as he would. The screenplay is by Dunja Gry Jensen and the director Henrik Ruben Genz. There’s something about the unusual setting and the dark, Scandanavian mood about the whole thing that is somewhat interesting in itself. It tries to be different, character and atmosphere rather than formula directed and I wanted to be involved. I’m also willing to concede that it was me and not the film. But I just couldn’t get that terribly happy about it.

Terribly Happy has an Oscar connection as well. It was Denmark’s official entry in the foreign film category. It wasn’t chosen, however. To be honest, I can’t say I’m that disappointed. It’s about a police officer in Copenhagen who pulls a gun on his wife when he catches her with another man. For recovery (and punishment), he’s sent to a very, very, very small town that has its own ways of doing things, like killing and dumping people they don’t like in a bog (it almost reads like a very, very, very serious version of Hot Fuzz). The officer is pursued sexually by the wife of the town alpha male and bully, who often beats her for flirting with other men. This leads to tragedy for the wife and bully who end up getting killed by the officer, crimes covered up by the town. From that summary, it sounds like my cup of tea. But Terribly Happy never grabbed me. I wasn’t always sure why. I know that at the beginning the officer comes across as so incompetent I had little interest or sympathy for him. He seemed over his head, but not because the town had its own set of rules, but because he didn’t know what he was doing. The killing of the wife seemed a bit forced and unintentionally funny. And the ending where the town joins forces to stop the officer from returning to Copenhagen by threatening to tell the authorities what really happened didn’t make sense to me. I didn’t know why they wanted to keep this guy around. He’s not the most popular addition to a party. And why you would want to have someone around who got away with killing two people is beyond me; after all, the more someone kills and gets away with it, the more likely he is to kill again. And the same people who didn’t want him to call the police after the wife died because secrets of the town would come out, not seem to suddenly have no problem going to the police themselves. What would they do if the officer called their bluff? They’d be in almost as much trouble as he would. The screenplay is by Dunja Gry Jensen and the director Henrik Ruben Genz. There’s something about the unusual setting and the dark, Scandanavian mood about the whole thing that is somewhat interesting in itself. It tries to be different, character and atmosphere rather than formula directed and I wanted to be involved. I’m also willing to concede that it was me and not the film. But I just couldn’t get that terribly happy about it.

No comments:

Post a Comment