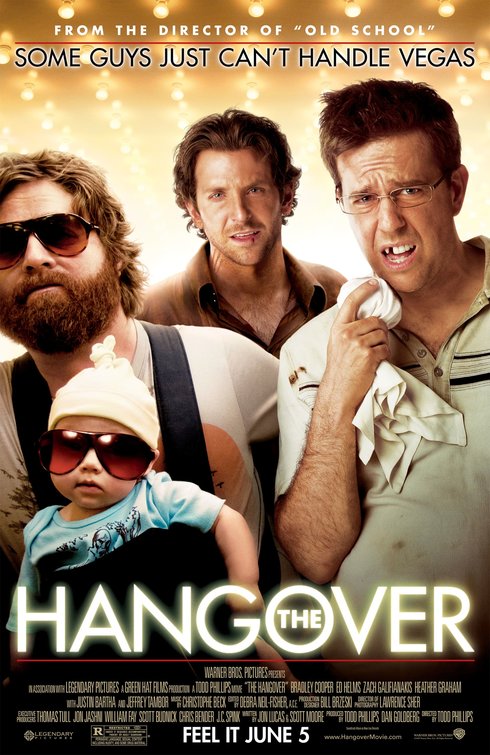

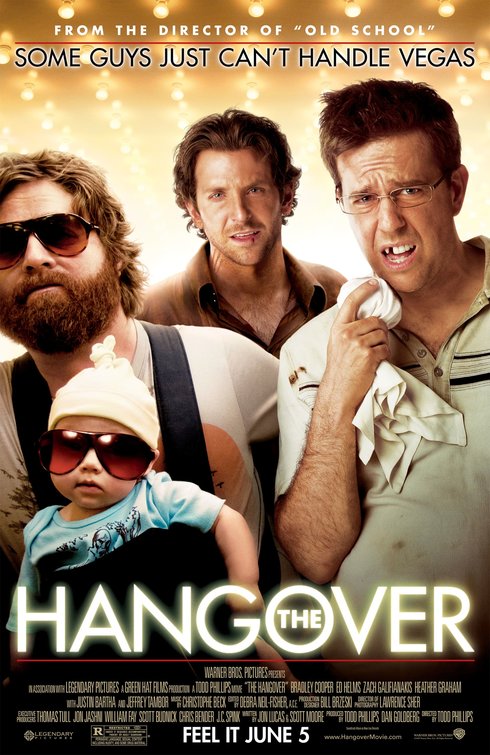

The Hangover is one of those high concept movies that studios love. Coincidentally, it also happens to be an interesting concept, a rare juxtaposition in Hollywood. It’s about four assholes who to Las Vegas on a bachelor party (actually, three, because the groom to be is actually a nice guy), and the next thing they know they wake up in a hotel room with a baby, a tiger, a missing tooth, a wedding ring…and the groom missing. What’s not to like? There are problems with the script. The first pleasure one hopes to derive from this farce is to see these idiots get their comeuppance, and they do for awhile (there’s one hysterical scene where they get tasered by the police). But in the end, they get away with everything they do with no serious repercussions, which is a bit of a disappointment; the authors, Jon Lucas and Scott Moore (among two others who are claiming they are not being given full credit), want to have it both ways—they want their characters to have arcs and be changed men while at the same time not having any arcs and not changing one iota. A bad idea aesthetically, but it probably contributed to the movie making as much money as it did. Many critics have complained that the story loses steam in the second half, and they’re right. At some point, it really stops building when it should be piling more and more on. A movie with a similar idea, Dude, Where’s My Car, doesn’t work as well overall, but it’s more imaginative and plotwise closer to what this movie should have been. This one’s still a lot of fun and it will be a long time before one forgets the nude Mr. Ken Jeong leaping out of the character’s car.

The Brothers Bloom is one of those con men films like The Sting, The Flim Flam Man, The Grifters, you get the drift. This one is very, very serious though, in spite of all the comedy. It’s about one brother who wants out of the game and one who thinks that keeping his brother in brings meaning to the brother’s life. The whole thing’s a mess and the plot never really makes a lot of sense by the time it’s over. Sorry to be so negative, but I really had a hard time following the damn thing, though I’m willing to admit it’s a “me and not you” thing. It’s directed in an “I’m the director and you’re not” style by Rian Johnson that probably obscures the real pleasure the script (also by Johnson) might have given one. Only Rachel Weisz as a classic 1930’s screwball heroine hits the mark here. She’s fun in a Katherine Hepburn/Carole Lombard sort of way.

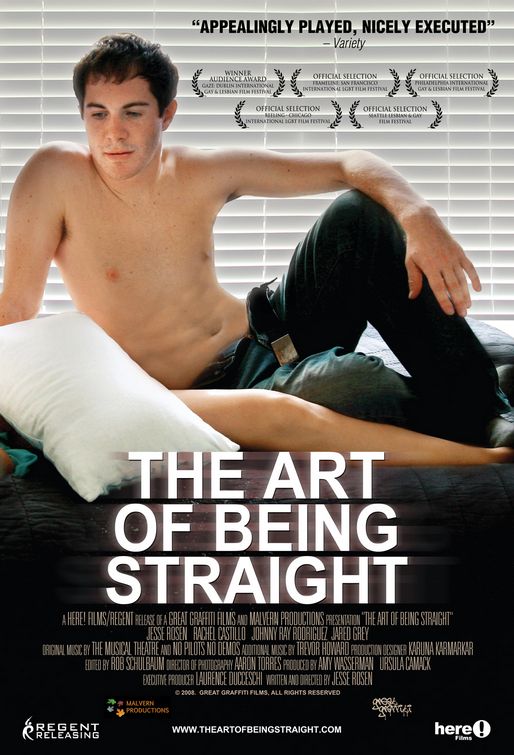

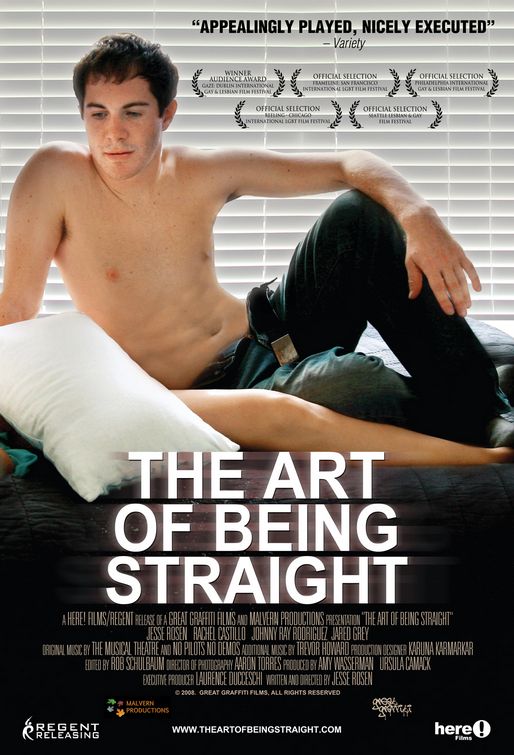

The Art of Being Straight is one of those movies that thinks it’s being daring and it might actually be if the same sort of themes hadn’t already been explored for years in earlier films. The ads and reviews suggest it’s about a man who’s bisexual, though the way it’s written (by Jesse Rosen), it’s actually about a man who’s gay and hasn’t come out of the closet. There was potential here for a movie about a man who has sex with another man, but doesn’t understand why. Unfortunately, the screenplay doesn’t deal much with that (though it may think it does). There’s a second plot about a lesbian who considers an affair with a man which makes a lot more dramatic sense and is much better written. The mumble core approach to the directing and technical values don’t help. It only makes it seem like the author and director hadn’t figured out what they were trying to do yet. Again, I’m sorry to be so negative, but I do get a bit frustrated when someone thinks their dealing with a new subject in a daring way, when it’s really a bit old hat. It’s one of my pet peeves and I don’t do a good job of not wearing it on my sleeve (to mix a metaphor). But when it comes to bisexuality, give me Love Songs, Y Tu Mama Tambien, When Night is Falling, Sunday, Bloody Sunday, Chuck and Buck, Chasing Amy and the films of Gus Van Zandt to name but a meager few. In the end, unlike Star Trek, the author here is going where many men have gone before.

The Hangover is one of those high concept movies that studios love. Coincidentally, it also happens to be an interesting concept, a rare juxtaposition in Hollywood. It’s about four assholes who to Las Vegas on a bachelor party (actually, three, because the groom to be is actually a nice guy), and the next thing they know they wake up in a hotel room with a baby, a tiger, a missing tooth, a wedding ring…and the groom missing. What’s not to like? There are problems with the script. The first pleasure one hopes to derive from this farce is to see these idiots get their comeuppance, and they do for awhile (there’s one hysterical scene where they get tasered by the police). But in the end, they get away with everything they do with no serious repercussions, which is a bit of a disappointment; the authors, Jon Lucas and Scott Moore (among two others who are claiming they are not being given full credit), want to have it both ways—they want their characters to have arcs and be changed men while at the same time not having any arcs and not changing one iota. A bad idea aesthetically, but it probably contributed to the movie making as much money as it did. Many critics have complained that the story loses steam in the second half, and they’re right. At some point, it really stops building when it should be piling more and more on. A movie with a similar idea, Dude, Where’s My Car, doesn’t work as well overall, but it’s more imaginative and plotwise closer to what this movie should have been. This one’s still a lot of fun and it will be a long time before one forgets the nude Mr. Ken Jeong leaping out of the character’s car.

The Hangover is one of those high concept movies that studios love. Coincidentally, it also happens to be an interesting concept, a rare juxtaposition in Hollywood. It’s about four assholes who to Las Vegas on a bachelor party (actually, three, because the groom to be is actually a nice guy), and the next thing they know they wake up in a hotel room with a baby, a tiger, a missing tooth, a wedding ring…and the groom missing. What’s not to like? There are problems with the script. The first pleasure one hopes to derive from this farce is to see these idiots get their comeuppance, and they do for awhile (there’s one hysterical scene where they get tasered by the police). But in the end, they get away with everything they do with no serious repercussions, which is a bit of a disappointment; the authors, Jon Lucas and Scott Moore (among two others who are claiming they are not being given full credit), want to have it both ways—they want their characters to have arcs and be changed men while at the same time not having any arcs and not changing one iota. A bad idea aesthetically, but it probably contributed to the movie making as much money as it did. Many critics have complained that the story loses steam in the second half, and they’re right. At some point, it really stops building when it should be piling more and more on. A movie with a similar idea, Dude, Where’s My Car, doesn’t work as well overall, but it’s more imaginative and plotwise closer to what this movie should have been. This one’s still a lot of fun and it will be a long time before one forgets the nude Mr. Ken Jeong leaping out of the character’s car. The Brothers Bloom is one of those con men films like The Sting, The Flim Flam Man, The Grifters, you get the drift. This one is very, very serious though, in spite of all the comedy. It’s about one brother who wants out of the game and one who thinks that keeping his brother in brings meaning to the brother’s life. The whole thing’s a mess and the plot never really makes a lot of sense by the time it’s over. Sorry to be so negative, but I really had a hard time following the damn thing, though I’m willing to admit it’s a “me and not you” thing. It’s directed in an “I’m the director and you’re not” style by Rian Johnson that probably obscures the real pleasure the script (also by Johnson) might have given one. Only Rachel Weisz as a classic 1930’s screwball heroine hits the mark here. She’s fun in a Katherine Hepburn/Carole Lombard sort of way.

The Brothers Bloom is one of those con men films like The Sting, The Flim Flam Man, The Grifters, you get the drift. This one is very, very serious though, in spite of all the comedy. It’s about one brother who wants out of the game and one who thinks that keeping his brother in brings meaning to the brother’s life. The whole thing’s a mess and the plot never really makes a lot of sense by the time it’s over. Sorry to be so negative, but I really had a hard time following the damn thing, though I’m willing to admit it’s a “me and not you” thing. It’s directed in an “I’m the director and you’re not” style by Rian Johnson that probably obscures the real pleasure the script (also by Johnson) might have given one. Only Rachel Weisz as a classic 1930’s screwball heroine hits the mark here. She’s fun in a Katherine Hepburn/Carole Lombard sort of way. The Art of Being Straight is one of those movies that thinks it’s being daring and it might actually be if the same sort of themes hadn’t already been explored for years in earlier films. The ads and reviews suggest it’s about a man who’s bisexual, though the way it’s written (by Jesse Rosen), it’s actually about a man who’s gay and hasn’t come out of the closet. There was potential here for a movie about a man who has sex with another man, but doesn’t understand why. Unfortunately, the screenplay doesn’t deal much with that (though it may think it does). There’s a second plot about a lesbian who considers an affair with a man which makes a lot more dramatic sense and is much better written. The mumble core approach to the directing and technical values don’t help. It only makes it seem like the author and director hadn’t figured out what they were trying to do yet. Again, I’m sorry to be so negative, but I do get a bit frustrated when someone thinks their dealing with a new subject in a daring way, when it’s really a bit old hat. It’s one of my pet peeves and I don’t do a good job of not wearing it on my sleeve (to mix a metaphor). But when it comes to bisexuality, give me Love Songs, Y Tu Mama Tambien, When Night is Falling, Sunday, Bloody Sunday, Chuck and Buck, Chasing Amy and the films of Gus Van Zandt to name but a meager few. In the end, unlike Star Trek, the author here is going where many men have gone before.

The Art of Being Straight is one of those movies that thinks it’s being daring and it might actually be if the same sort of themes hadn’t already been explored for years in earlier films. The ads and reviews suggest it’s about a man who’s bisexual, though the way it’s written (by Jesse Rosen), it’s actually about a man who’s gay and hasn’t come out of the closet. There was potential here for a movie about a man who has sex with another man, but doesn’t understand why. Unfortunately, the screenplay doesn’t deal much with that (though it may think it does). There’s a second plot about a lesbian who considers an affair with a man which makes a lot more dramatic sense and is much better written. The mumble core approach to the directing and technical values don’t help. It only makes it seem like the author and director hadn’t figured out what they were trying to do yet. Again, I’m sorry to be so negative, but I do get a bit frustrated when someone thinks their dealing with a new subject in a daring way, when it’s really a bit old hat. It’s one of my pet peeves and I don’t do a good job of not wearing it on my sleeve (to mix a metaphor). But when it comes to bisexuality, give me Love Songs, Y Tu Mama Tambien, When Night is Falling, Sunday, Bloody Sunday, Chuck and Buck, Chasing Amy and the films of Gus Van Zandt to name but a meager few. In the end, unlike Star Trek, the author here is going where many men have gone before.

No comments:

Post a Comment