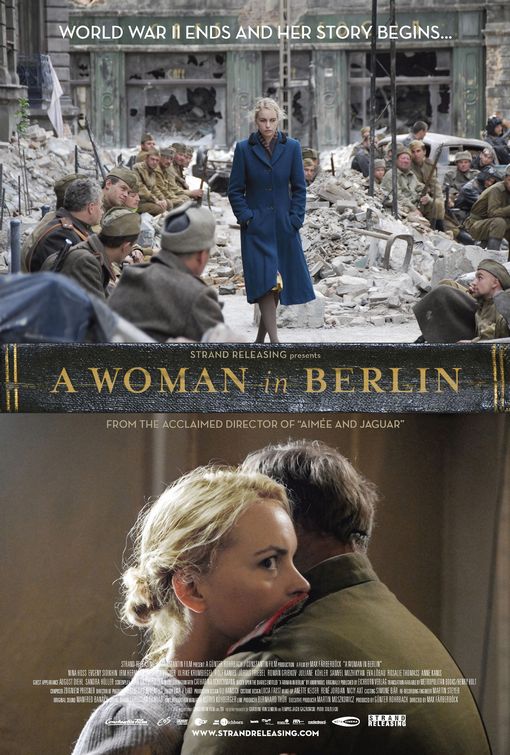

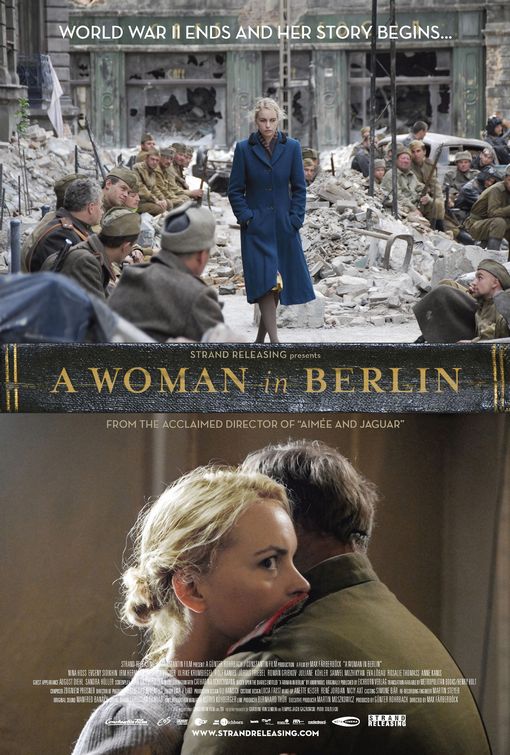

A Woman in Berlin is hardly what the previews prepare one for. The coming attractions suggest a hard hitting expose, ripped from the headlines type movie about a sordid bit of WWII history, a story that has been more or less ignored in histories of the time: the rapacious use of women when the Russians marched into Berlin at the end of the war. It’s not that it’s not about that, but in reality, this awful situation is really more the backbone of the story rather than the gist of it. For when all is said and done, this is really an old fashioned 1930’s star crossed romance. I may get in trouble for saying something as outrageously inhumane as this (of course, no one really reads this blog, so who’s going to know), but it’s the type of movie that once upon a time would have starred Greta Garbo or Marlene Dietrich with Adolphe

Menjou, at his oily best, as the man she gives herself to in order to survive; her husband would have been played by an

nonthreatening leading man like Herbert Marshall. It’s one of these new movies (like

Blackbook and Flame and Citron) which is suppose to be a revisionist look at the morality of WWII where we are asked to reconsider the idea of bad guys and good guys. This is a perfectly acceptable idea, but the revisionism is a bit hunt and peck in this movie as written by the director Max

Farberbock and co-writer Catharina

Schuchmann. Though a couple of atrocities committed against the Russians are mentioned in passing, one would never know that six million Jews died at the hands of the German (one wants to muddy the waters, but not muddy them too much it seems). In spite of all this, there is much worth seeing here. The subject matter is important and the leading lady is German actress of the moment, Nina (

Yella, Jericho)

Hoss. And the fate of the star crossed lovers at the heart of it does leave one with a tear in the eye.

Julie & Julia is that movie about Julia Child and another real person that

isn’t as famous. I could repeat the usual analysis of it in which people point out the story line with Julia Child (brilliantly portrayed by Meryl

Streep; poor girl, she actually has to go to the Oscars again) is great, but the part with Amy Adams, a good actress stuck with a dull, uninteresting character,

isn’t so much so (it’s even hard to understand, based on the excerpts read aloud in the movie, why anybody even read her blog). Instead I’ll focus on an odd through line that I found somewhat disturbing. For a movie that has two women as central characters, the movie as a whole

doesn’t have much positive to say about women as a whole. In the screenplay by director Nora

Ephron, there are two kinds of women. There are the friends of Julie, high powered businesswomen played at the height of soullessness in their best Faye

Dunaway/Diane

Christiansen manner by an assortment of actors. They’re the bane of Julie’s existence and ridiculed mercilessly by

Ephron. The other kind of women, the ones that

Ephron seems to approve of, are nonthreatening, never even considering doing a man’s job. For Julia, it’s to take a cooking class without the goal of becoming of chef and then writing a cook book; for Julie, it’s writing a blog about cooking and then writing books. Nice, safe womanly things to do (even in Julia’s world, the male chefs are accepting and encouraging, it’s the female who runs the cooking school herself who is the gorgon). Though on the outside this movie would seem to be an antidote to the misogynistic turn of romantic comedies like The Proposal and The Ugly Truth, once the surface is scraped away, it’s not really that much different.

A Woman in Berlin is hardly what the previews prepare one for. The coming attractions suggest a hard hitting expose, ripped from the headlines type movie about a sordid bit of WWII history, a story that has been more or less ignored in histories of the time: the rapacious use of women when the Russians marched into Berlin at the end of the war. It’s not that it’s not about that, but in reality, this awful situation is really more the backbone of the story rather than the gist of it. For when all is said and done, this is really an old fashioned 1930’s star crossed romance. I may get in trouble for saying something as outrageously inhumane as this (of course, no one really reads this blog, so who’s going to know), but it’s the type of movie that once upon a time would have starred Greta Garbo or Marlene Dietrich with Adolphe Menjou, at his oily best, as the man she gives herself to in order to survive; her husband would have been played by an nonthreatening leading man like Herbert Marshall. It’s one of these new movies (like Blackbook and Flame and Citron) which is suppose to be a revisionist look at the morality of WWII where we are asked to reconsider the idea of bad guys and good guys. This is a perfectly acceptable idea, but the revisionism is a bit hunt and peck in this movie as written by the director Max Farberbock and co-writer Catharina Schuchmann. Though a couple of atrocities committed against the Russians are mentioned in passing, one would never know that six million Jews died at the hands of the German (one wants to muddy the waters, but not muddy them too much it seems). In spite of all this, there is much worth seeing here. The subject matter is important and the leading lady is German actress of the moment, Nina (Yella, Jericho) Hoss. And the fate of the star crossed lovers at the heart of it does leave one with a tear in the eye.

A Woman in Berlin is hardly what the previews prepare one for. The coming attractions suggest a hard hitting expose, ripped from the headlines type movie about a sordid bit of WWII history, a story that has been more or less ignored in histories of the time: the rapacious use of women when the Russians marched into Berlin at the end of the war. It’s not that it’s not about that, but in reality, this awful situation is really more the backbone of the story rather than the gist of it. For when all is said and done, this is really an old fashioned 1930’s star crossed romance. I may get in trouble for saying something as outrageously inhumane as this (of course, no one really reads this blog, so who’s going to know), but it’s the type of movie that once upon a time would have starred Greta Garbo or Marlene Dietrich with Adolphe Menjou, at his oily best, as the man she gives herself to in order to survive; her husband would have been played by an nonthreatening leading man like Herbert Marshall. It’s one of these new movies (like Blackbook and Flame and Citron) which is suppose to be a revisionist look at the morality of WWII where we are asked to reconsider the idea of bad guys and good guys. This is a perfectly acceptable idea, but the revisionism is a bit hunt and peck in this movie as written by the director Max Farberbock and co-writer Catharina Schuchmann. Though a couple of atrocities committed against the Russians are mentioned in passing, one would never know that six million Jews died at the hands of the German (one wants to muddy the waters, but not muddy them too much it seems). In spite of all this, there is much worth seeing here. The subject matter is important and the leading lady is German actress of the moment, Nina (Yella, Jericho) Hoss. And the fate of the star crossed lovers at the heart of it does leave one with a tear in the eye. Julie & Julia is that movie about Julia Child and another real person that isn’t as famous. I could repeat the usual analysis of it in which people point out the story line with Julia Child (brilliantly portrayed by Meryl Streep; poor girl, she actually has to go to the Oscars again) is great, but the part with Amy Adams, a good actress stuck with a dull, uninteresting character, isn’t so much so (it’s even hard to understand, based on the excerpts read aloud in the movie, why anybody even read her blog). Instead I’ll focus on an odd through line that I found somewhat disturbing. For a movie that has two women as central characters, the movie as a whole doesn’t have much positive to say about women as a whole. In the screenplay by director Nora Ephron, there are two kinds of women. There are the friends of Julie, high powered businesswomen played at the height of soullessness in their best Faye Dunaway/Diane Christiansen manner by an assortment of actors. They’re the bane of Julie’s existence and ridiculed mercilessly by Ephron. The other kind of women, the ones that Ephron seems to approve of, are nonthreatening, never even considering doing a man’s job. For Julia, it’s to take a cooking class without the goal of becoming of chef and then writing a cook book; for Julie, it’s writing a blog about cooking and then writing books. Nice, safe womanly things to do (even in Julia’s world, the male chefs are accepting and encouraging, it’s the female who runs the cooking school herself who is the gorgon). Though on the outside this movie would seem to be an antidote to the misogynistic turn of romantic comedies like The Proposal and The Ugly Truth, once the surface is scraped away, it’s not really that much different.

Julie & Julia is that movie about Julia Child and another real person that isn’t as famous. I could repeat the usual analysis of it in which people point out the story line with Julia Child (brilliantly portrayed by Meryl Streep; poor girl, she actually has to go to the Oscars again) is great, but the part with Amy Adams, a good actress stuck with a dull, uninteresting character, isn’t so much so (it’s even hard to understand, based on the excerpts read aloud in the movie, why anybody even read her blog). Instead I’ll focus on an odd through line that I found somewhat disturbing. For a movie that has two women as central characters, the movie as a whole doesn’t have much positive to say about women as a whole. In the screenplay by director Nora Ephron, there are two kinds of women. There are the friends of Julie, high powered businesswomen played at the height of soullessness in their best Faye Dunaway/Diane Christiansen manner by an assortment of actors. They’re the bane of Julie’s existence and ridiculed mercilessly by Ephron. The other kind of women, the ones that Ephron seems to approve of, are nonthreatening, never even considering doing a man’s job. For Julia, it’s to take a cooking class without the goal of becoming of chef and then writing a cook book; for Julie, it’s writing a blog about cooking and then writing books. Nice, safe womanly things to do (even in Julia’s world, the male chefs are accepting and encouraging, it’s the female who runs the cooking school herself who is the gorgon). Though on the outside this movie would seem to be an antidote to the misogynistic turn of romantic comedies like The Proposal and The Ugly Truth, once the surface is scraped away, it’s not really that much different.

No comments:

Post a Comment